Incorrigibles

Interview with Alison Cornyn

Arlene Tucker

Edited by Anastasia Artemeva

На русском языке

Incorrigibles is a transmedia project that tells the stories of ‘incorrigible’ girls in the United States over the last 100 years – beginning with New York State. The teams draw on the personal narratives of young women in “the system” to investigate the history and present state of youth justice and social services for girls. An online oral archive is currently being developed, based on the stories of young women affected by incarceration. Art and drama workshops encourage personal participation and deeper understanding of people self identified as girls in confinement - now and in recent history.

Arlene Tucker met with Alison Cornyn, the director of the project, to learn more about her motivation, inspiration and process.

Alison in her studio. Image: Arlene Tucker

HOW IT STARTED

Arlene Tucker (AT): Alison, thank you for meeting with me. Could you start by telling me a little bit about the project?

Alison Cornyn (AC): Hi Arlene! So the research for the project started back in 2011 and it wasn't titled Incorrigibles then. I started the Prison Public Memory Project with a colleague when Governor Cuomo of New York said he was finally going to close seven state prisons because economically they didn't make sense. Having worked around mass incarceration and criminal justice issues for many years, starting with a documentary back in 2001 called 360degrees.org (Perspectives on the US Criminal Justice System), I realized that US communities that have a prison, very often have a kind of knee jerk reaction when the prison is set to close. Thinking that the prison provides economic development, they want to keep it open and either make it a private prison or a jail so its funding is from a different budget. Rather than considering what could be more healthy for the community it feels more comfortable to maintain the status quo. So we started thinking if we could work with communities before the prison closed and help them research how it got there in the first place that they could create a process to envision what they wanted to see in its stead when it closed.

So we started working in Hudson, New York thinking that the medium security men’s prison there - Hudson Correctional Facility - would close. As it turns out it didn't close. But in the process of researching it I realized that it had opened in the late eighteen hundreds as a women's House of Refuge. And then from 1904-1975 it became what was called The New York State Training School for Girls which is really a euphemism for a young woman's prison. It housed girls age 12 to 18 and they would often stay for two years or more. There were as many as 500 girls there at any time. In 1975 it became a medium security men's prison. I was doing an installation on the prison grounds in a mansion that used to be the superintendent’s house called the Bronson House. The superintendent who had been there in the 1970s had moved out because he felt it was too opulent - the girls had to work as servants to clean the place and keep it up. So he moved to a smaller house on the grounds with his family and this place fell into disrepair.

AT: And what is the purpose of the house now?

AC: Historic Hudson is trying to keep it from from falling into further disrepair. They have rented it out as a movie set so they could use those funds to stabilize it. I don’t believe that they want to make it a museum but more of a meeting space and they would like to create a park around it. This plan is a little difficult because the house is still on the prison grounds and it’s still a functional prison. What makes it even more complicated is apparently there's a shooting range on the grounds where the local police practice shooting. So on weekdays between 2 and 4pm no one can go in that area because there's the possibility of a stray bullet.

The house is open twice a year because Historic Hudson offers architecture tours there as the building is architecturally notable. And I asked if we could do an installation in in the space as the architecture tours went on. So around the time I was trying to figure out what the installation would be, because often I use technology in art works but there was no electricity so we had to keep things really simple. Around that time there was a thrift shop owner in Hudson who goes to various yard sales to find clothing and other old items to sell in her store. And she found a box of documents at a yard sale that she bought for five dollars. It turns out that the contents of the box were documents that had been spirited out of the New York State Training School for Girls in the 1920s and 30s. There were intake forms, medical records, letters, and photographs of girls.

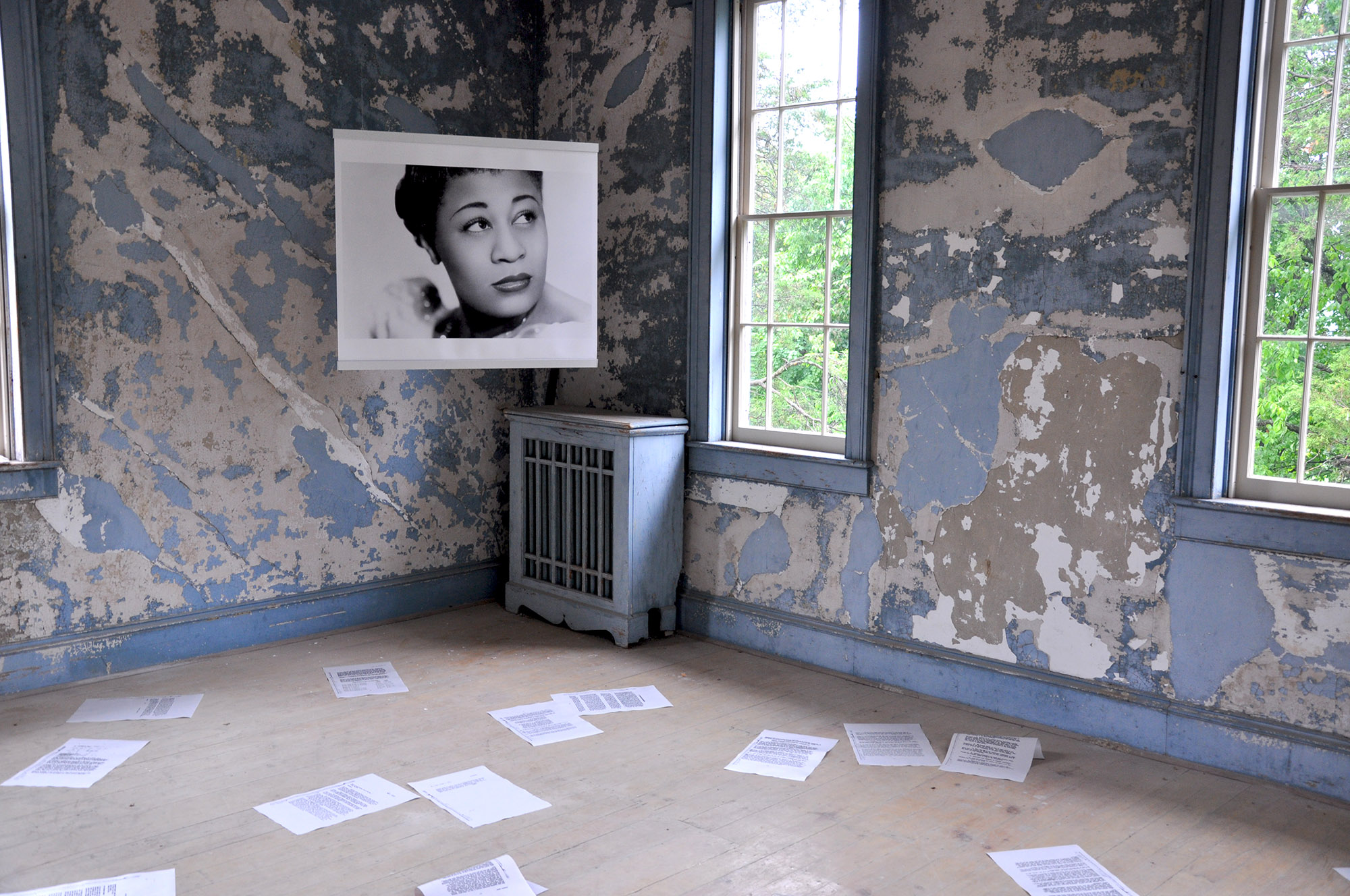

Image: Arlene Tucker

She shared those documents and I started piecing together which documents related to which girls and threading their stories together. And so the installation that I ended up doing in the Bronson House was based on the pieced-together stories of six of the girls. I also learned that Ella Fitzgerald, the famous singer had been at this institution in the 1930s around the same time that the these other girls were there. So (in my installation) Ella got her own room and each of the girls got their own room. I created larger-than-life portraits on archival paper that hung from the ceiling and then recreated the documents from the box and strew them around on the ground in the same way that they'd been left to the dust of history to probably be destroyed like most of the other documents from the institution.

Image: https://incorrigibles.org

In the course of doing this installation and working with these documents I realized that for me it was really important to tell the stories of these girls and make sure that their lives weren't lost/forgotten. As I was going through the documents it became clear that many of the girls were physically abused, sexually abused, and they are the ones that were sent away rather than the abusers. And then in one case, the girl was 12 years old and her mother and stepfather ran a boarding house and they married her off by selling her to one of the boarders. So her parents were eventually arrested and sent to prison for selling this girl; their daughter. And she was sent to an orphanage. And there she was talking about being married at 12 and having sex at 12 and the staff said that she was going to ‘corrupt the morals’ of the other children in the orphanage. So she was then sent to the Training School - this kind of prison like space to protect the other kids who she had been talking with. And what's interesting is when she gets there, there's a copy of a letter she wrote home, it's a letter to her mother where she asks about how her grandparents are and talks about how when she got to the place they played games and it's almost as if she's not acknowledging what happened to her. And I don't know if somebody was looking over her shoulder telling her what to write or if she was in denial about what had happened to her. Those kinds of questions I think remain to be understood. So I started thinking about how we can understand what's changed and what's not for young women who are incarcerated or end up in the social service system in the US.

Image: Arlene Tucker

As I started putting some of the research online I was taken by the lives of these girls and I decided rather than continuing to work on the project about prisons closing in communities and reinvigorating things I wanted to do a project about the past, present and future of young women's incarceration in the US.

And so Incorrigibles was born out of their stories and those documents. I started putting research online on a simple website and then people started writing in who would say: "I was at this place" because it didn't close till 1975. So the girls whose stories were in the box from the ‘tens, ‘20s, ‘30s have all passed away, including Ella Fitzgerald. But there were women from the 60s and 70s that wanted to tell their stories. And also people were writing in because now with all the genealogical search programs people were finding that they had mothers and grandmothers and aunts who had been at this place and they want to know what it was and why they were there. So I was helping write Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) letters to the New York State Archives, but there’s not much left in the archives for the most part in terms of the records. I think that most of them were destroyed.

INCORRIGIBLES

The name of the project came about because for so many of the girls were deemed “incorrigible”, this one woman Lyla in particular - her offence was being “incorrigible”. I remember I photographed Ella Fitzgerald's intake record for Nina Bernstein who wrote for The (NY) Times (and who is the person who found that Ella had been at that institution). Ella's offence was being "ungovernable, and will not obey the just and lawful commands of her mother - adjudged delinquent.” So what's interesting is that at the time she was sent there from what I understand her mother had passed away. She was living with an abusive stepfather or an aunt and an abusive uncle. And like many girls even today when there is abuse happening in the household very often they run away. In the States arrests for those kinds of acts are called status offences where if you're not an adult, a status offence like running away, being truant from school (where if you're older than 18 would not be grounds for incarceration) can get girls sent away. So I started doing oral history interviews with women that were writing in and wanted to share their stories.

Ella’s Room: If These Walls Could Talk...

Site-specific exhibition at The Bronson House in Hudson, New York

Image: https://www.alisoncornyn.com/

Ella’s Room: If These Walls Could Talk...

Site-specific exhibition at The Bronson House in Hudson, New York

Image: https://www.alisoncornyn.com/

I was really interested to try to understand what was happening in their lives and in the lives of their families before they were at the Training School, and what it was like at this place. And since then - what's that they've gone on to do. And the stories are so so so different, as are the women, and they're amazing. And for the most part the women want to share their stories with young women today who may be going through similar things to let the them know they're not alone. Because in so many cases there was a silencing that still happens through fear and intimidation and feeling like you don't have power.

Workshop with young women based on Incorrigibles’ documents. Image: https://incorrigibles.org

AT: And not understanding why they were sent away, how can they talk about that?

AC: Some authorities had a sense that by the girls running away they were acting out and had to be locked up. What is becoming more focused on today is not the actions but why; why people are doing those actions like if somebody is acting out, if they're angry, if they're running away, if they're not going to school, why are they doing that? There's something going on with them personally and very often in their families. That's what needs to be dealt with. And rather than the girl being punished for that action, because the action isn't the problem is to address the root cause. So that's beginning to be understood more. But still there's quite a way to go I think before we really can deal with all of the issues that young women face.

One woman Liz who was sent to the Training School for being incorrigible, talked about not knowing what that word meant and looking it up many many years later. But basically she was angry and she admits to being angry but she was separated from her family. There were five siblings when she was about seven years old her grandmother died. The house was lost, then her mother passed away. Her father was alcoholic. And so the kids all went to the Catholic Charities that picked them up, put them in foster homes. She was sent to a home all by herself and there she was physically and sexually abused. She talks about how she became angry that she would act out all the time because she was not able to protect herself. And there's all these things happening to her. Her life was very difficult. When she got out she ended up marrying her pimp and was in an adult prison eventually for what may have been an attempted murder. But she came out and what's amazing about Liz. She also had substance abuse issues. She began to be involved with 12 step programs. And so every day she would go to a 12-step meeting. And when she passed away her partner invited me to her funeral. There were hundreds of people there. And so many people were telling stories about her and how she had been kind of a mentor to so many people and she had touched so very many lives when she was alive.

Another woman who was sent to the Training School when she was young is Lillian. I'm trying to help her find her sentencing records. She was living in the Bronx at the time and apparently her records were in a warehouse that recently burnt down. And so we're still trying to see if that's true because she doesn't know why she was sent away. And she wants to understand her sentence because she was being sexually abused by her father. And she started talking about it to a friend's mother and the next thing you know she's being kept home from school. And so she's truant. And she is sent to the Training School because she's not going to school -- but she's not allowed to go to school. So she wants to know what her father said about her and what the judge deemed as her offence so that's still in process.That was in either of the late 60s or the early 70s. Her inquiry is still in process.

LANGUAGE

AC: Language is so important to this project and the language of how a young woman is deemed something. Even the term incorrigible sounded so old fashioned to me I didn't think it was used anymore and then I looked up just to double check: “unable to be reformed or corrected”. Research has shown that 70 percent of those (incarcerated) girls (in New York) are marked today still as incorrigible. And I had wanted to have young women be involved when the exhibition was up at the Bronson House and almost stand in for the women who are no longer with us but whose stories need to be shared.

We did theatre workshops and sociodrama workshops and I was really interested in this investigation of language and for the girls to do their own research into archival documents because how often you get to do that? So I told them some of the stories of the girls and they decided whose story they wanted to investigate further. And they got packages of documents and they would get together and create simple theatrical scenes based on these girls’ lives and on their own.

What I'm really interested in is the language that people outside of the girls use to define them and confine them. And so the girls were really interested in that too so we came up with this list of words that were used yesterday and today through these documents but also in their own personal experience to label them and what words they wanted to use to define themselves. And that's become a huge part of this project because of self-definition. And that kind of ability to speak for yourself is so important.

These are the words that the girls came up with that they found or that were used to define them, (by others): wild, unruly, defiant, wayward, delinquent, disobedient, incorrigible, ungovernable.

And then these are the words that they used to define themselves and these other girls who they were researching: free, proud, strong, survivor, imaginative, determined courageous and free spirited.

There was a performance that we invited the public to and then we had a community conversation where the girls led the conversation about youth justice then and now, whatever anybody wanted to talk about in relation to that.

We recently reached out to organizations that are working with young women around the country who are doing writing programs and arts programs. And the first piece we received is incredible: It's from a woman who's in prison, not in New York, but she said that throughout her youth she was called an “abomination”. She was a young person growing up in the 90s and she was a boy who wanted to be a girl. And so the term abomination came from that. Everywhere she went that was the word that people would use to define her.

And now she is irrepressible.

And that's the word that she uses for herself.

THE SCHOOL

At the New York State Training School for Girls there were as many as 15000 girls that did time there over the period that it was open. There were as many as 550 or 600 girls at a time at its height. The age would be eleven to sixteen and sometimes a few years beyond that.

And very often the girls would stay there for two years. I've asked the women about what kind of training there was and from what I understand there wasn't much by way of academics. There was home economics, there was sewing, there was cooking, furniture making, bookmaking. Some women talk about the abuse there and how horrible it was. When Ella Fitzgerald was there in the 1930s the institution was segregating the black girls into two of the cottages and having them do all the laundry and much of the work. There was a lawsuit that was brought against the institution by the NAACP and others and they had to stop the segregation practices. Ella Fitzgerald was invited back by the superintendent in the 1970s to perform or meet the girls and she said she wanted nothing to do with the place. It had been a really bad part of her memory and her history.

And so there was the use of solitary confinement. There were a lot of things that aren't healthy that we know of.

AT: And what about recidivism rate?

AC: That's a really good question. In these books where you can see when each girl went in you can see if girls were sent back or somehow ended up back there. Actually one of the women I interviewed who was there in the 70s said she was there twice. The way it works is very often there would be a home visit and if the home wasn't a safe place to return to they would be paroled to a job, and especially in 20s and 30s, a job as a mother's helper or as a maid in a hotel, or some kind of service job. And in some cases you see that the girls would run away from the job or they would burn the ironing or cooking.

And in one case there's a girl who was sent back. She was a mother's helper and that woman says "she burns the toast. I can't do anything with her" and then she was enrolled as a maid in a hotel. Was she doing that on purpose so she could be free? You really wonder. But the girls when they were paroled, at least back in the 20s and 30s (because we have these documents), they would have to write letters back to the institution every month and list how much money they made, what they spent it on, and report on what their month was like. So it turns out a lot of girls went on to get married because then they wouldn't have to report back to the institution.

AT: One question came to mind: I'm thinking, is this also part of learning social skills, of how to get along with others? From an educator perspective that's what came into my mind.

AС: If they had the proper staff they could have facilitated that and it could have been really helpful for some of the girls. Some of the women I spoke with talk about how they benefited from being there. It wasn't all bad. Some people said it was a stable environment. “I learned how to cook” or how “my grandmother was an incredible seamstress” or they were taken out of a really abusive situation that they were trying to run away from but they didn't know where to go. And then others talk about the abuse and the lack of of proper care, punishments and those kinds of things. So there was both, though it also depends on the girl and the time of their life, and who was around her. I mean an eleven year old is completely different from a 16 year old. Many women who were there talk now about the need back then for more therapeutically trained staff. But that wasn’t understood by the institution.

PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE

AC: Together with an intern, Maansi, we had gone through an ancestry database and we've put in around twenty five hundred names. Because in the census, starting in 1905 to 1945, in Hudson at the Training School, all those girls were listed as ‘inmates’. And even some of their babies were listed in the census as inmates as some girls were sent there because they were pregnant. And so you have this inmate who is point five years old (6 months old).

So this information is on our website. And people are seeing that a relative was at the NY State Training School. They want to talk about that -- either to understand more what that place was like or to share the story of that family member. I recently met with a woman who's based in Florida but she was in New Jersey for a family reunion and her great grandmother was at the Training School in 1910. We spoke about the generational impact of a young woman's incarceration. And in her case it was generations of institutionalization - from orphanages to mental institutions to continued incarceration. And she's really interested in the generational impact of trauma and trying to map that out. Studies about that are being done around neuroscience and epigenetics and I want to include these as context on the website.

AT: How do you connect the past, the present and the future ?

AC: Whenever we do an exhibition our goal is to also do a public program -- and these really are about connecting the past and the present; the future. The exhibition in Troy, NY which was called “Dislocations: artists respond to mass incarceration” included artists working with people who've been incarcerated in various ways - they asked me to do a public program and an amazing artist Beth Thielen facilitated it with me.

Wands

Image: Arlene Tucker

The first wand-making workshop was at the Hunter Gallery and people were invited to make wands for themselves or for women who have been in the Training School. So we made some amazing ones. Liz is the woman who was separated from her family and sent to an abusive foster home when she was very young. When I had an early conversation with Liz she spoke about how she never had a childhood and she never had a tiara. She never had a princess costume. She never did dress-up. She never had Christmas. She never got presents. She never had what she thought was a proper childhood. I decided to make a wand for Liz and wanted to include things that could represent the childhood she dreamed of. And I put little things on it that were very like those things she'd talked about having missed - little charms. And the sad thing is I was never able to give her the wand as she passed away before I could give it to her. I brought it to her memorial service and I gave it to her partner who loves the wand.

There's something about creating a wand to reclaim your power. It's a different kind of a storytelling device. And potentially a therapeutic one.

Image: Arlene Tucker

ALISON

AT: And what about you? I realised I don't know about your history and how you got here.

AC: I think the criminal justice interest/involvement came from when I had gone to graduate school at NYU’s Interactive Telecommunications Program. I'd completed the program and was starting to use the web as a space for storytelling about (social) issues. I started a studio called Picture Projects with Sue (Johnson) who was in graduate school with me. I had read a book called "The Real War on Crime" edited by a lawyer named Steven Donziger. It looked at the state of the criminal justice system in the US and some of the essays compared the choices the U.S. had made, in relation to other countries. And you could see that the trajectory of incarceration had gone up exponentially from the 1970s of under 200,000 people to by the early 2000s when the 2 millionth person was about to be incarcerated.

360 Degrees

Image: https://www.alisoncornyn.com

So we thought that the issue of mass incarceration encompassed so many other social issues of race, class, economics, education in the US that we decided we were going to do a documentary about the criminal justice system. And people thought we were insane. It's a very large topic and nobody knew what a web documentary was really -- because it was 2000. The Web hadn't been out for that long. And we ended up creating this site called 360degrees - Perspectives on the U.S. Criminal Justice System. The heart of the site was stories told from five or six different people involved around one person's incarceration: person in prison, guard, family member, victim's family, social workers, judges, wardens, corrections officers and these stories were told from all these different people's’ perspectives, which complicated the stories. You need to be able to hear where different people are coming from and the only way we're going to really be able to move forward is to be able to understand why somebody feels so passionately about their own way of thinking and to acknowledge that and then move forward, in addition to the systemic issues involved.

It was in 2000 and in 2001 and I learned that the two millionth person was about to be incarcerated in the US. And I was really struck by that number and how huge it was. But then also by how statistics hit you and then they kind of wash over you and you don't know what to do with them anymore. So in parallel with 360 where we were doing interviews and photographing and creating documentary work, I went to Coney Island and I filled a bag of sand and I decided I was going to count two million grains of sand to really understand how much that meant. I brought it back to my apartment. I ended up counting for two weeks and I counted 10,000 grains of sand in those two weeks - a full time job. Iit filled up a straw, about four inches; a drinking straw.

And so I realized that in order to really understand the prison population it would be important to count the population of the world. And then I would need to bring people in to count because it would be impossible for one person to count in a lifetime. So I started a project called The Sand Counting Laboratory. I was on a residency in the Czech Republic in an old monastery. There was this architectural space that was hexagon shaped with huge arched windows and I filled the floor with sand and placed just a table in the middle of the room. I had a video counting off the real time population of the world, a clock and then another digital counter counting the prison population. People could come in, put on a white lab coat, sit at the table, and count sand. People would come in and just do that.

Sand Counting Lab, Site Specific Installations, Bitola, Macedonia

Image: https://www.alisoncornyn.com/

Sand Counting Lab, Site Specific Installations, Bitola, Macedonia

Image: https://www.alisoncornyn.com/I realized in the process though that rather than trying to get to two million or reach any one number that it's constantly in flux, that it would be more important as a process piece and as a place to think about the issues than to try and reach the goal of getting to the number 2 million which was problematic to begin with. So I ended up not keeping the sand that was counted. At the end of an installation it would go back into the pile.

It was kind of absurd. Initially I always had a little magnifying glass which helps to see the sand but not totally clearly. So in the University of Michigan I chose to put the installation in a greenhouse in the Life Sciences Building. And when one of the scientists came in and I explained this project he said “You need a microscope”. The next thing I know I went in the next day and there was this big Leica microscope in the lab. So the students used that to count and it was really amazing what they were able to see. The final iteration was a seven foot cube steel room - a New York Sand Counting Lab. This seven foot cube volume is the amount of space that the 6 billion at the time population of the world would take up in Coney Island grains of sand. And seven feet - that same volume - is what's given to a person in a prison cell. And then people could come in and count, and on the outside there was the population of the world being counted. I was introduced to someone who was working at the Museum of Natural History to do scanning electron microscope - sand portraits - of individual grains to show how unique they are really and how they need to be attended to.

Sand Counting Lab

Installation view, Parrish Art Museum, Southampton, NY

Image: https://www.alisoncornyn.com

Sand Counting Lab

Installation view, Parrish Art Museum, Southampton, NY

Image: https://www.alisoncornyn.com

INCORRIGIBLES WANT TO HEAR YOUR STORY

Have you been described as something you’re not? By a judge, the police, your teachers, your parents, or any other authority in your life? Have they tried to tell you that you’re a criminal or a delinquent; out of control, crazy, wild, disrespectful, or otherwise bad?

Head over to https://incorrigibles.org/your-incorrigible-story/ and tell about the words that have been used to define and confine you, just what you think of them, and how you define yourself.

Image: https://incorrigibles.org

Image: https://incorrigibles.org

You can support the Incorrigibles project here https://incorrigibles.org/store/