suomeksi

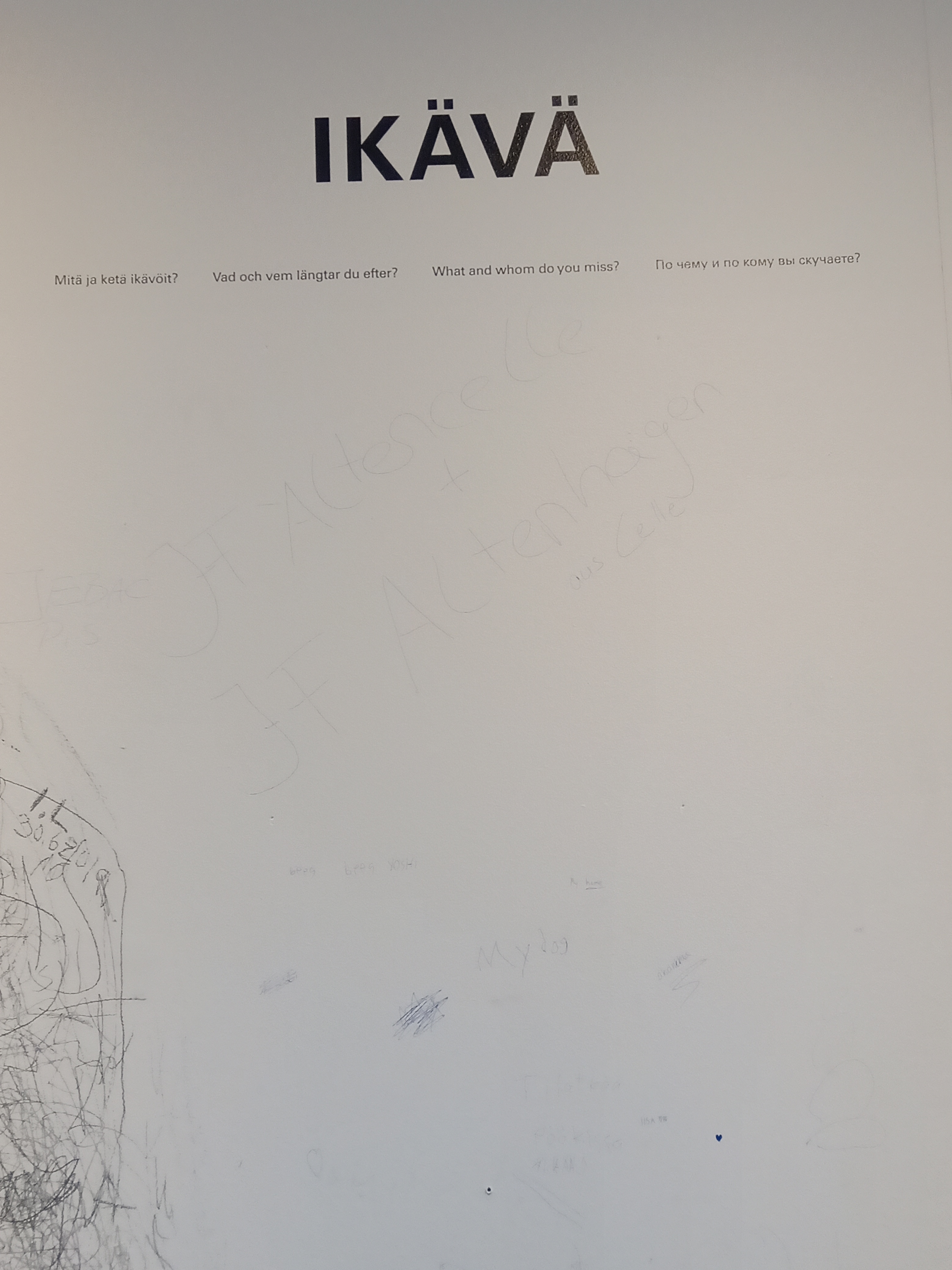

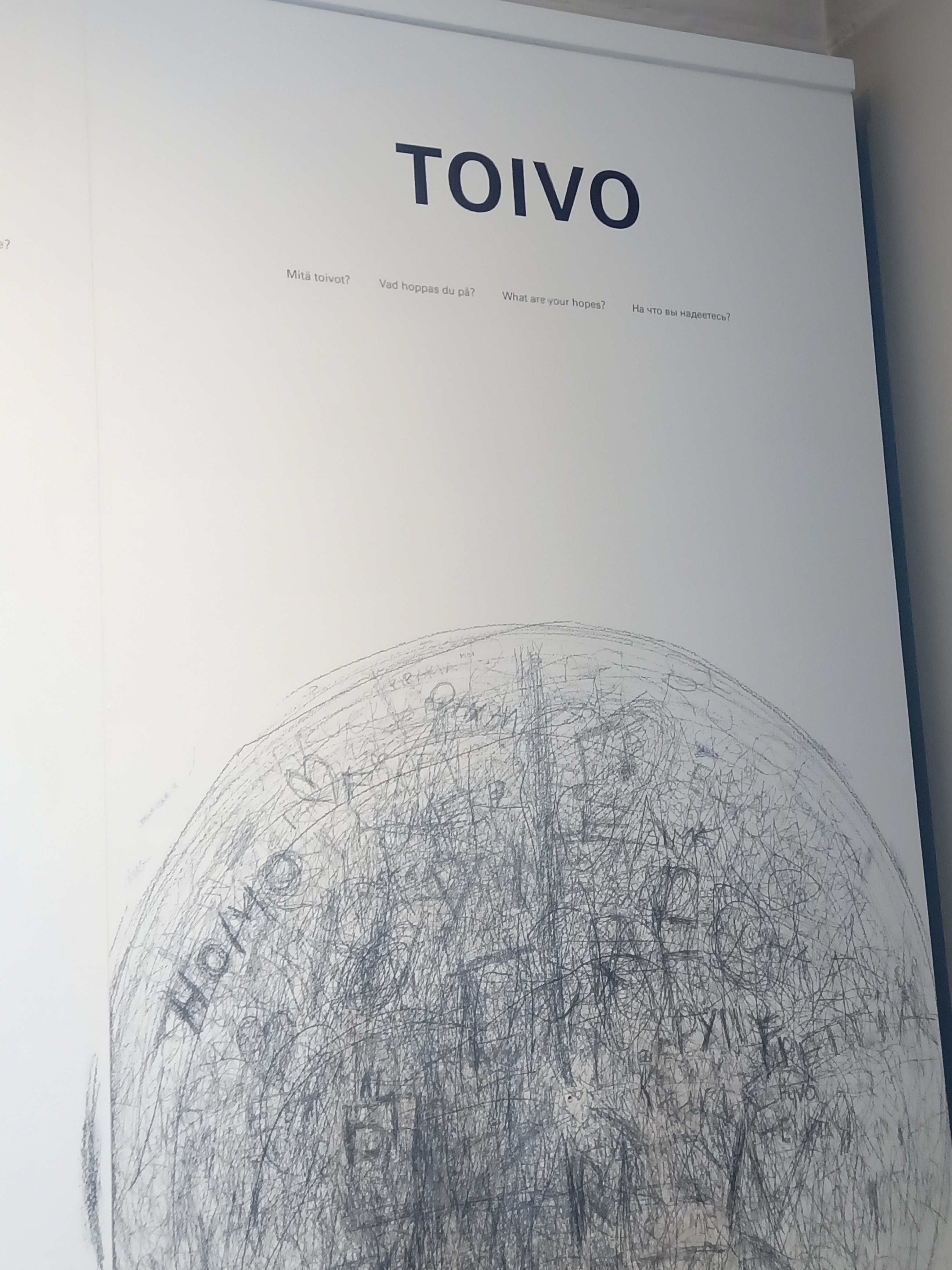

After a long korona break we get to meet with people again. Prison Outside and Free Translation held a #freetranslation workshop in Mikkeli. Persons who have experienced incarceration have generously shared stories and made artistic responses to the free translation works.

The artworks are live on the free translation site https://freetranslation.prisonspace.org/?id=

and will be part of an interactive art exhibition at Mikkeli Train Station 23.-29.5.22.

We are very greatuful to our partners:

MIELI Mental Health Finland https://mieli.fi/en Mikkeli sudivision https://www.mielenterveysseurat.fi/mikkeli/

Support service for men in Mikkeli, Finland http://miestenasema.fi

Source text: Jyrki Heikkinen - Imagination is a gate and will is a threshold stone. Mielikuvitus on portti ja tahto on kynnyskivi., 2019

Translations made during a Mental Health Art Week 2022 workshop in Mikkeli:

Marianne: “Kaksi vanhaa puuta ja 8+1 taimea” 10.5.22, pastelliliitu

Eveliina – Elämän sävyt ja kerrokset, 10.5.2022

Source text: Gaylen Grandstaff "The Real Mishka" - Without Justice 2, Between July 18, 2017 - March 18, 2019

Translations:

Anna: “Fenix” 10.5.22, pastelli

Timoфei: “Usko ja toivo rakkaudesta” 10.5.22, pencil, oil pastels, pastel.

Please see the full online gallery at

https://freetranslation.prisonspace.org/?id=

Mitobira design project in prison, Japan

https://3tobira.or.jp

I zoom with the Mitobira project directors on a Saturday morning right in the middle of the scorching Tokyo summer. As Chiaki Yamabe, Makiko Matsuo, Satoko Asan Makiko Tamaki prepare for the official launch of their tapestry collaboration in Tokyo University of the Arts, we are joined by Rika Fujii from Arts Initiative Tokyo

Summer in Japan

Summer in JapanGeneral Incorporated Association Mitobira,

(Representative director Shoji Fujimoto) started 3 years ago as a partnership between the ministry of justice of Japan and a fashion business. Government operation public facility, private finance initiative, as well as crowdfunding has been used to have the project sustainable.

This is a very exciting time - on the other side of the screen a package is being opened. Inisde are traditional style carrier bags, made from silk kimono fabric. These are designed and made by incarecerated women by the women participants of the project. The bags are beautiful and look very practial. I inquire about the price but it hasn’t been decided yet.

Another example of the products designed and produced as part as Mitobira project are womens tops - a fusion of traditional Japanese fabric with a western design twist. They are stylish and they are quality.

The overall aim of the project is to create a possibility for the women who are affected by the system to develop design eye, learn sewing skills, and upon release from prison have established a network and an opportunity to continue their employment.

Mitobira fashion design (image: Mitobira)

Mitobira fashion design (image: Mitobira)As we chat online, my room shakes and the checked windows rattle. A truck passing by on the road? I look at my zoom mates, their knowing faces and worried voices - an earthquake! It’s a small one. On we go with our discussion.

First sales of the goods are to a hotel as amenity goods. The pieces will be available for the general public to purchase once the prices are calculated. The directors will set up an online shop.

Mitobira fashion design (image: Mitobira)

Mitobira fashion design (image: Mitobira)Prison facilities often have sewing workshop equipment set up, and in the cases where they do not, the team has provided donated machines and irons. Operator training and creating printed manuals have been a large undertaking for the team. This is to make sure that everyone can learn and work the sewing machines, the overlocks and the drafting sets.

Tama juvenile detention facility, Tokyo

Tama juvenile detention facility, Tokyo Pioneers in design, craft, technology, Japan has recently begun to open to socially engaged creative practices that welcome persons living in institutions. It is an exciting time for those artists who have worked hard for many years to make these changes happen.

This project is an example of women to women solidarity: “Many people return to crime because they don't have the money to start when they enter the workforce. Those who serve short sentences do not receive adequate training. They are useless when they enter society. At Mitobira, women are encouraged to improve their sewing skills. I want them to be skilled enough. I want them to make it their job from now on.“

A fashion store in Tokyo

A fashion store in TokyoMost women who serve a long sentence are involved in a production or training organized by the correctional institution. Work possibility varies on the sentence length and the person's abilities and skills. Some of the goods are sold to the general public through an online shop. What makes Mitobira different is that they aim to provide skills for the incarcerated women to develop and after the release continue to work or set up their own business.

“The reason why we use kimono is to convey Japanese culture. We want to create meaningful products. We want to be known as a fashion brand, rather than as something made in a prison. We want to convey this to the people in prison. We want them to have confidence in themselves and to increase their value.”

”NIJIMU”

The world blends together through art, and from the words of an artist named Katsuhiko Hibino, the message of the brand.

Fabric store, Nippori Fabric town, Tokyo

Fabric store, Nippori Fabric town, Tokyo Artist Anastasia Artemeva is a recipient of a Residency travel grant from Finnish cultural foundation and Artist Initiative Tokyo. Her research visit to Japan took place in June-August 2023.

Prisons turned into art spaces and closed again #1

Limerick, Ireland

Anastasia Artemeva

Many thanks to Andrew Kearney and Deirdre Power

На русском языке

Some governments close prisons because of the centralisation and improving of the conditions. Some countries have achieved such low crime rates, that spaces of incarceration are no longer needed. Some places opt for creating large industrial complexes. Victorian red brick beauties as well as the brutalist giants from the 1980’s are no longer needed. Some are knocked down, some remain silent monuments to architectural achievements, some are repurposed.

One of the new functions of the spaces of compulsory confinement is museums, art exhibition spaces and studios. It can be said that the architecture itself already invites such a response as prisons and museums have similarities both in design and in function, both made to be holding, containing somebody or something.

View from the prison building onto the river Shannon. Andrew Kearney, 1983/84.

View from the prison building onto the river Shannon. Andrew Kearney, 1983/84.Image courtesey of Andrew Kearney.

Prison Space will publish a series of notes on such spaces. This selection of prisons turned art spaces covers a variety of realised and proposed projects that make former prisons into spaces for arts. What unites them, as this is only a short list of such, is that their role as an art space hasn’t lasted. They gave way to housing, local government buildings, or standing idle waiting for an investor. In these articles we attempt to analyse what can be done to a space once its original function has ceased. We look at methodologies used to give these former places of suffering a new purpose and a new context. The temporality of the projects does not reflect on their success. These played a significant role in activating the spaces, and uniting the stakeholders through it’s brisk action. What is the meaning of a prison building within the local and global history and social geography.

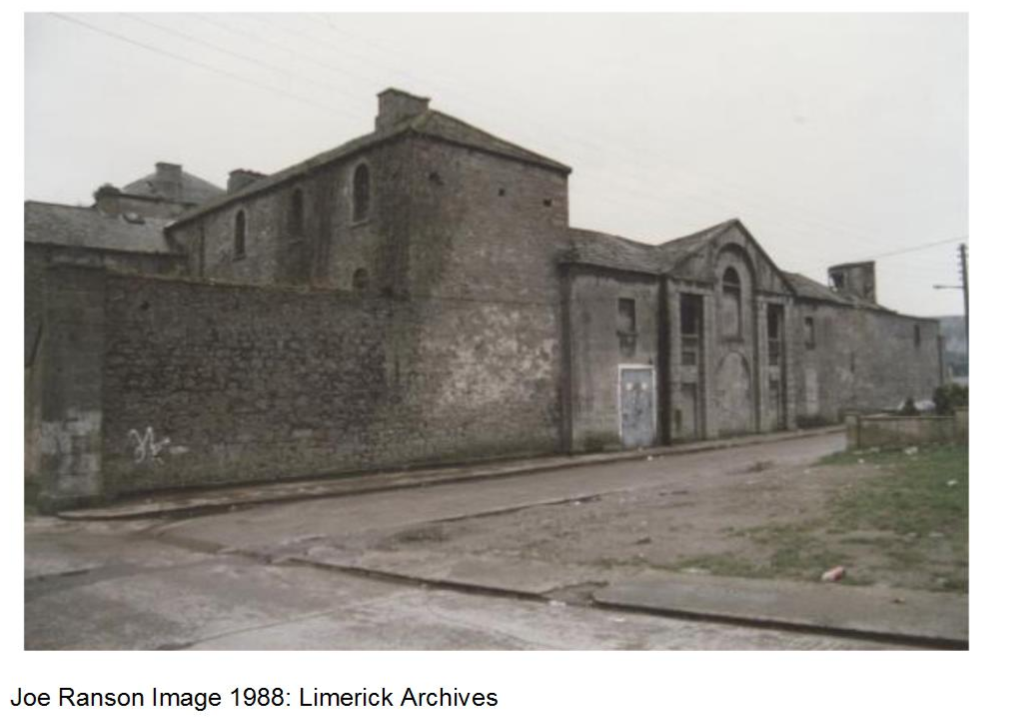

First stop is Debtor’s prison in Limerick, Ireland. Limerick is a city in the West of Ireland, located on the River Shannon, where the river widens before it reaches the Atlantic Ocean. Founded by vikings, and ran subsequently by waves of invading normans and anglos-saxons, the city has an industrial working-class history and a rich cultural heritage.

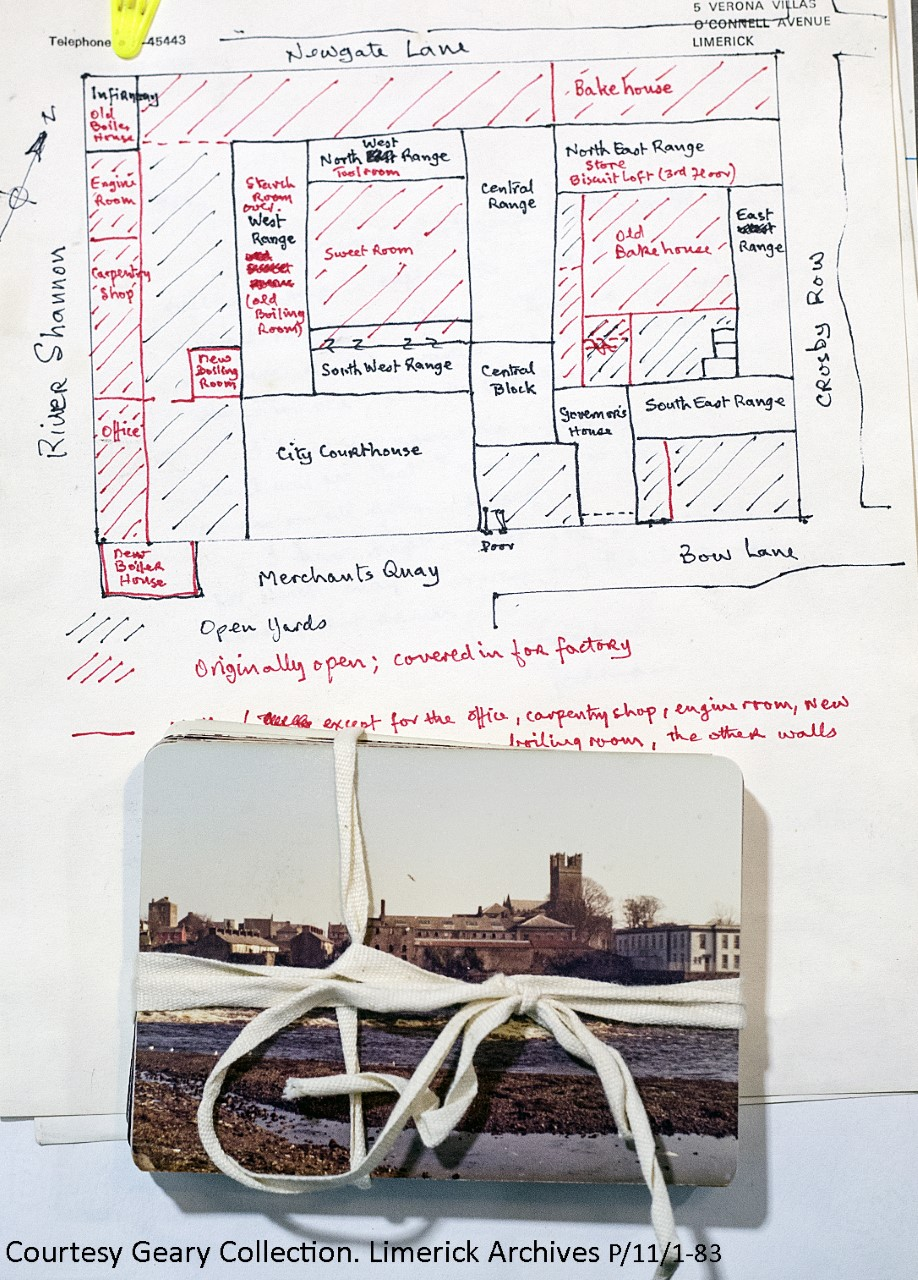

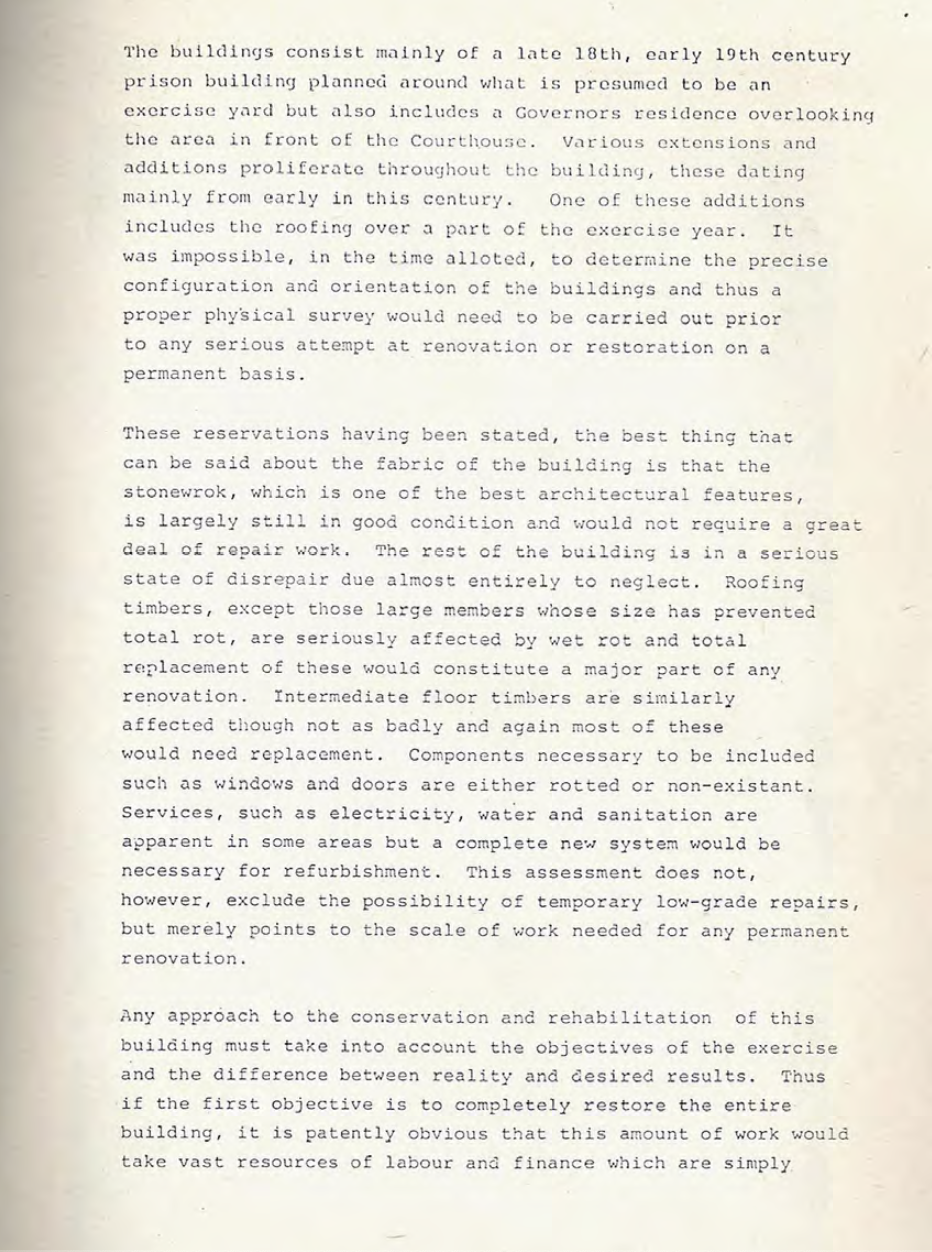

Material sourced by Deirdre Power from the Limerick City Archives on the later history of the building as a biscuit & sweet factory. The documents & photographs were compiled by the last of the Geary family.

Material sourced by Deirdre Power from the Limerick City Archives on the later history of the building as a biscuit & sweet factory. The documents & photographs were compiled by the last of the Geary family. At the time of construction of the prison - in the late 18th century/early 19th century Ireland was under the British rule, and its penal practices reflected those in the United Kingdom. Severe laws allowed for capital and corporal punishment, as well as shipment of prisoners to penal colonies in America, Australia to name a few. When this practice was being abolished and prison reform was under development, new places to detain arrested persons were needed. New correctional facilities were designed, essentially similar to the ones that are used today.

Material sourced by Deirdre Power from the Limerick City Archives on the later history of the building as a biscuit & sweet factory. The documents & photographs were compiled by the last of the Geary family.

Material sourced by Deirdre Power from the Limerick City Archives on the later history of the building as a biscuit & sweet factory. The documents & photographs were compiled by the last of the Geary family. The building constructed on the bank of the river Shannon in the early 19th centry was used as a Debtor’s and Women’s prison - a place of incarceration not for criminals as such, but for people who were not able to pay their debts. Failure to pay even a small sum could result in imprisonment, not only for the persons in question but also for their families. Moreover, the incarcerated person was obliged to pay fees to prison officials, often significantly higher than the original debt itself, which resulted in even longer sentences.

Timeline :

1813: The prison building was complete, with a stage for executions at its front.

1902: The building was repurposed as Geary’s Biscuit factory, operated in the premises on Merchant’s Quay.

1922: Irish Free State is created, marking the process of formation of the Republic of Ireland.

1982: The factory closes.

1984: A group of students from Limerick School of Art and Design proposed to turn Limerick Debtors & Women’s prison into a new art space, creating a “center for visual and performing arts”. Their aim was to provide working and exhibition spaces for recent graduates, and provide better connections with the public, particularly with school students. Visual artists Deirdre Power and Andrew Keirney shared their experiences in negotiating with the then Limerick Corporation, now Limerick City & County Council to convert the disused prison into an art and creative space. Andrew Kearney documented the building in 1983/84 and recorded among others drawings scratched on the walls of the cells that look like they were done in the 20's during the civil war in Ireland as it's of armoured tanks in the streets as kids play around them ( the drawings were executed by one of the daughters of Geary’s, who ran the factory - Limerick City Archives).

All + 10 Sorts Acrhive Artists Collective Limerick

Proposal and a report from arhitect Brian Thompson.

Their proposal was denied. Nonetheless, the collective re-grouped, determined to find suitable space to work. They met with Jack Ormston, of Ormston Supermarket and negotiated a yearly renta over head the top floor of the Ormston supermarket, No 9,10 & 11 Patrick Street, Limerick. This was the first artist-led space, supported by The Arts Council of Ireland, outside the capital, Dublin.

1988: The prison building was demolished.

1990: City Hall completed on the vacant space. Parts of the existing structure including the underwater drains and quays can be seen outside city hall on the riverside. The original entrance/facade to the prison is visible from outside street, Crosbie Row.

2015: The artist collective - All + 10 Sorts group’s proposal from 1984 was revisited with the archive exhibited to the public through the Third Bridge exhibition in Ormston House. Ormston House is a cultural resource center established in the former supermarket.

Material sourced by Deirdre Power from the Limerick City Archives on the later history of the building as a biscuit & sweet factory. The documents & photographs were compiled by the last of the Geary family.

Further reading:

ALL + 10 SORTS ARCHIVE ARTIST COLLECTIVE LIMERICK 1983 Proposal

Third Bridge (1983/2015) archival project/exhibition by Andrew Kearney and Deirdre Power

21 August - 18 September 2015, Ormston House Cultural Resource Center, Limerick, Ireland.

Third Bridge Publication. Accompanying the exhibition, the artists have produced an 8-page newspaper publication which includes archival documentation of the project in 1983, a text and timeline by historian Prof. John Logan, and related newspaper articles.

http://ormstonhouse.com/programme/third-bridge-1983-2015-andrew-kearney-deirdre-power/

Eurostat https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/crime/overview

Day, J., Corrections and collections. Architectures for art and crime, Routledge, 2013

B. Henry, Dublin Hanged: crime, law enforcement and punishment in late eighteenth-century Dublin, 1994

https://www.historyireland.com/18th-19th-century-history/prison-reform-in-ireland-in-the-age-of-enlightenment/

Limerick Chronicle, Sat 20th, 1969 http://www.limerickcity.ie/media/pris008.pdf

Anastasia Artemeva

6th Abramkin Readings

Prison Conference

Moscow,

19 May 2020

Resocialization of sentenced prisoners: practices, experiences and problems of the emergency situation of the year 2020.

The 6th Abramkin Conference focused on the problems of the reintegration of currently and formerly incarcerated individuals. The event brought together more than 50 prominent Russian and international speakers. Experts from the Commissioners for Human Rights in the constituent entities of the Russian Federation, human rights organizations, representatives of the legal community, attorneys of non-profit organizations with experience working with prisoners, and representatives of relevant federal departments took part in the conference. First-hand experiences of incarceration were also presented. The event took place via Zoom platform as gathering of people were restricted due to Covid-19 pandemic.

As an introduction, friends and colleagues - journalists, lawyers, human rights activists and criminology and psychology experts, including Zoya Svetova and Galina Kozlova spoke about Valery Abramkin. Abramkin served six years in prison in the 1980's for producing and disseminating Samizdat publications. After the release Abramkin established the Center for prison reform and dedicated his life’s work to the reformation of Soviet and later Russian prison until he passed away 8 years ago.

Zoya Svetova spoke about Valery Abramkin

Zoya Svetova spoke about Valery Abramkin

Numerous questions and challenges were discussed at the conference - from the lack of adequate information to the person awaiting release and assisting the reintegration process, to the need for coordinating the efforts of various services for resocialization and the interaction of state and public institutions. A particular focus was on the challenges brought about by the Covid-19 pandemic.

Overall, a strong need for cooperation between the different institutions that can assist a prisoner upon release was noted. This includes governmental as well as non-for-profit organisations, charities and volunteers. The process of reintegration into society should begin already in prison, to ensure the incarcerated individual does not lose touch with family and social structures on the outside, however, while also encouraging him or her to separate from criminal connections and lifestyle. It should mean supervision, control and assistance, in prison and post release. There is currently no state fixed probation mechanism and resocialization organ. It is proposed the FSIN, the Russian Federal Prison Service (FSIN, Russian: Федеральная служба исполнения наказаний (ФСИН)) can adapt these works, but without any extra funding. The need for information on housing and employment opportunities to be available to individuals before the release was noted also by the speakers with personal experience of incarceration. Empirical research on the benefits of support systems before and after release would be beneficial and its findings should be incorporated into developing further structures and relative legislation. The existing laws should be implemented and their application monitored.

Andrey Babushkin, chairman of the Permanent Commission of the Presidential Council for Human Rights, offers a historical perspective. “The problem of rehabilitation came about with the establishment of prison. In the past, in the Soviet Union times, local authorities had the responsibility to house and employ persons within 10 days upon release. However in the mid-nineties the experience of the past years was lost as the short-lived system as Correctional and Social Rehabilitation Service was abandoned in 1991 and replaced by the current FSIN, The Federal Penitentiary Service, managed by the Russian Ministry of Justice.”

Personal factors play an important role. Eduard Mikhailov, Moscow Regional Public Organization for the Promotion of Social Adaptation of Citizens “the Ark, speaks of his experience. “For me, reintegration is, first of all, the readiness of a person who has left prison to abandon the criminal way of thinking. I personally didn’t achieve this understanding for a long time, you can say it took me about 50 years. I have been released, and again committed crimes repeatedly. If a person wants to live free, conditions will contribute to this decision, and he will meet the right people along the way.”

The 6th Abramkin conference took place via zoom

The 6th Abramkin conference took place via zoom

BEFORE THE RELEASE

Noted by many of the speakers was the importance of preparation for the release and assisting the prisoner in understanding the challenges he or she will face upon release, and how to overcome these challenges. Andrei Babushkin noted the difficulties one faces in the very first steps on the path to freedom: the Schools for preparation for release in correctional institutions of the FSIN do not cover the most important challenges that people face after leaving prison. These include paying bills, finding work, and accessing social services, among others. He suggested developing a unified program of courses, taught while the person is still serving a sentence, that prepares him or her for life outside of prison. Babushkin spoke about the loss of the basic skills of independent decision-making already one year after being in custody, meaning that most men and women leaving prison need full-fledged social support. However, this group of citizens is not included in any state social assistance programs.

Some of the participants expressed the point of view that it is not only the state and society that are responsible for the re-adaptation of the person returning from prison, but the individual must take on obligations to adopt the norms and values of civil society. It is important to facilitate participation and encourage one to change. We must take into consideration the factors that challenge the process of resocialization, research of the motivation to change, which depends, among other factors, on whether the person is a repeat offender. Psychotherapeutic treatment needs to be made available, rather than only the psychological support that exists in correctional facilities now. In response, human rights defender Valentin Gefter, noted that when speaking about reintegration we must include both those men and women who will challenge their criminal behaviour as well as those who will not, as nevertheless they all will re-enter society.

The involvement of civilians, psychologists, and creative practitioners, especially those who come from outside of the prison system has a positive effect on the wellbeing of incarcerated men, women and children. Marina Klescheva, documentary theatre Theatre.Doc, reflected on her personal experience of participating in acting and drama projects while serving a sentence in the Oryol women's colony. She pointed out that developing better communication between the prisoners and the staff of the institutions was an important aspect of the prisoner’s well-being. This was done with the professional experience of psychologists and artists. Olga Romanova, Jailed Russia spoke about the lack of clear legislation about who is allowed the access to prisons in russia.

Workshops of Hope, peer support group for people affected by incarceration, Theatre.Doc

Workshops of Hope, peer support group for people affected by incarceration, Theatre.DocPavel Mikov, Commissioner for Human Rights in the Perm Krai region, emphasized the importance of providing safe and clean space for long visits and polite professional prison staff during arranging long visits of the family. These issues affect social ties. Inability to live with the family in the open prisons (even though the law allows for it). Zagorskaya Elena, Moscow State University of Psychology and Education (MSUPE) , notes the evidence of the positive influence of the values of fatherhood and family on the personality of men serving sentences in correctional institutions and their social adaptation after release. At the same time, negative and disorienting environmental factors may turn out to be much stronger than constructive intentions to correct and adapt to life in society, this threatens to transfer the norms and principles of communication received in prison into subsequent family life after release. In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is necessary to take additional measures to organize remote communication using different communication tools which include written communication, both in paper and in electronic form, voice communication - telephone calls, including using voice services via the Internet and video calls, also via the Internet. A “video appointment” is equivalent to a telephone conversation and is not a substitute for visitation.

YOUNG OFFENDERS

Effects of incarceration on young people were discussed at the conference. Juliana Nikitina, the Vasily the Great Center, St. Petersburg, proposes that the problem of justice and the execution of sentences for minors should be discussed in the court system and the Federal Penitentiary Service. The placement of young people in detention centers and remnant prisons should be avoided altogether or limited to several days. The children who spend time in the pre-trial detention center are distinguished by the resulting trauma, increased aggression, distrust of adults, and they are susceptible to criminal tendencies as a result of being exposed to communities with antisocial leanings. Aleksandr Nazarov, Head and Professor of the Department of Criminal Procedure and Criminology of the Siberian Federal University, emphasises the importance of educational, rather than correctional, institutions for young offenders, in order to not to expose the children to prison traditions and subcultures. Everything must be done so that pupils do not continue their way into the adult prison after they turn 18.

To limit the possible incarceration for an underage person to less than six months and encourages methods offered by restorative justice instead. Was also discussed by Ivan Chebotarev, student of Mikhail Debolsky (MSUPE). Ivan presented research work on self-harm and autoaggression in young people in incarceration. Prevention of self-harm in places of detention is an important component of the work on the reintegration of prisoners, as acts of self-harm by juvenile prisoners while in a pre-trial detention center or serving a sentence in an educational colony will complicate their resocialization after release. First of all, this is due to the possibility of consolidating such behaviour - having committed an act of self-harm in a pre-trial detention center or a colony, a minor, in the absence of the necessary psychological work, and also, with certain actions of the administration (indulging a minor, or, conversely, excessively harsh sanctions), may learn that by committing self-harm, one can achieve any personally significant goals, or strengthen his authority in a criminal group that is reference for him, respectively, the use of such a "tool" will seem effective for a teenager even after his release. Research shows that most acts of self-harm have been carried out within the first two weeks within the institution, or within the following six months. To reduce the risk of self-harm the availability of psychological support needs to be increased, and more physical activity introduced.

The Vasily the Great Center is the only non-governmental organization in Russia that operates as a facility as an alternative to imprisonment and accepts adolescents on probation by the court; children stay there from 9 to 18 months. They study, play sports, much attention is paid to creative implementation, psychologists, psychotherapists, social workers are engaged with them, comprehensive work is being conducted to accompany both the child and the family. Over 16 years, 368 people passed through the Center, from those - 42 people committed offences again.

AFTER INCARCERATION

Alexei Sokolov, Yekaterinburg, NGO Legal Basis, noted the destructive effects of institutionalisation, one of which is when a person loses the ability to attend to own basic needs and act independently.

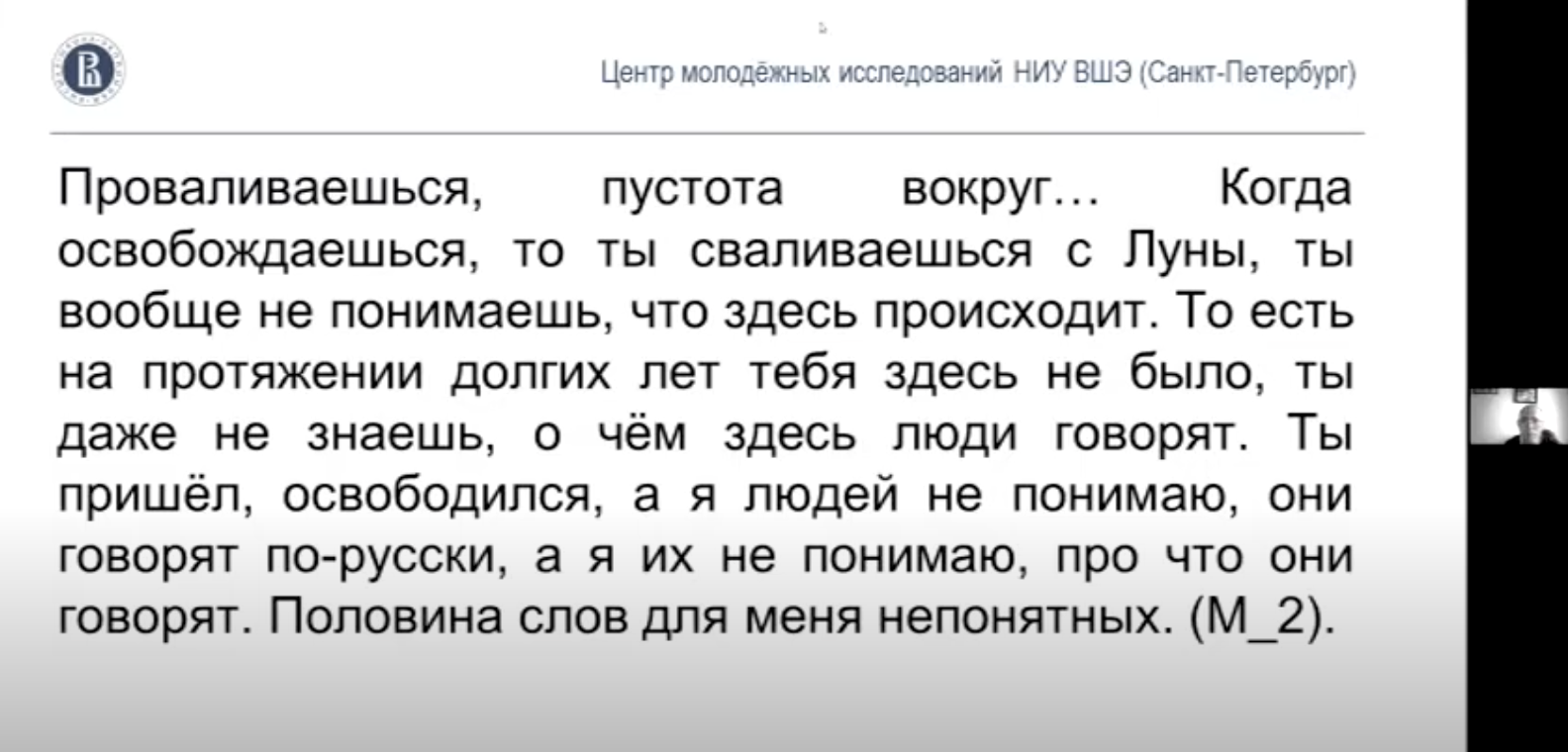

Iskender Yasaveyev, Higher School of Economics, presented interviews where men and women reflected on their experiences in the months and years after their release from prison:

A still form Iskender Yasaveyev‘s presentation

A still form Iskender Yasaveyev‘s presentation Making a choice - even in a grocery shop, it’s difficult to make a choice.

My family rejected me, they didn’t let me into my home.”

I wasn’t able to cross the road when I got out.

It’s difficult to learn. I’m learning to drive, but I just can’t remember what the road signs mean.

You are an outcast, your sentence, it stays with you forever

It’s like running up the escalator that is going down, or swim upstream

EMPLOYMENT AND HOUSING AFTER RELEASE

The complexities of daily tasks as well as processes such as seeking employment and securing accommodation were discussed at length. Anton Shtykov, Office of the Commissioner for Human Rights in Moscow, noted a lack of information for service and support available. For example, in 2019 171 people applied to the employment service in Moscow after their release. This is a very small amount, and it seems that there is a latency of numbers. Similar situation is in the Moscow region, as noted by Anatoly Tikhomirov, representative of the Commissioner for Human Rights in the Moscow Region. Alexey Yunoshev (Office of the Commissioner for Human Rights) There are 200,000 people annually released in Russia, 35% of them don't have permanent residence, more than 50% have problems with employment and quality of life. In Russia there are only 200 centers of social adaptation (shelters), which is far too little.

Some institutions for social assistance are run by the state and some are run by charities, both religious and civil. Conditions for being granted accommodation vary from institution to another. For instance, some places emphasize the prohibition of alcohol. Some offer accommodation for several nights, some for up to one year, for instance in the state-run Social adaptation center that Elena Bukhalovskaya spoke about. Representatives from rehabilitation facilities noted the importance of providing housing without the restriction on duration, as for the many people, suffering from alcohol and drug addiction, a long time is needed to overcome said addiction and to reintegrate into society. Ksenia Runova, (the European University at Saint-Petersburg) noted that the specific shelters for people released from prison are provided by the government only in several regions, including Krasnoyarsk. She adds that there is currently no legislation that ensures that people with a criminal record are provided with secure employment.

Pavel Mikov, Commissioner for Human Rights in the Perm Krai region, where in 28 institutions there are 17 000 incarcerated people, with 4 000 released annually, of which 100 are minors. The rate of repeated offence is high due to lack of housing, supporting documents and employment. A pilot project took place in 2009-2010. The goal was to ensure employment by granting 5 000 rubles to the employers hiring formerly incarcerated individuals in their home region. This was done to encourage the prisoners to return to the home area rather than continue to live in the proximity of the prison where they served the sentence.

Suzanna Kirilchuk, is the director of the non-governmental Social Rehabilitation Center Aurora that provides assistance for 150-200 women a year. The work is carried out in several directions: psychological assistance (for example, it is difficult for children to understand why their mother was away for so many years), legal (compiling complaints and petitions). Training courses, particularly the training in current and applicable specialties (florist, dog and cat grooming). It is very important to obtain new skills, to master computer courses, to learn the legalities of self-employment. She spoke about challenges in working with formerly incarcerated women. One such recurrent issue is a lack of self-motivation. Family is the primary source of motivation for self actuation. Often women need to reestablish a connection with their family, which the Center facilitates through the organisation of events. An example of such an institution/organisation is Healthy Generation (“Здоровое поколение”) located in the Krasnodar Krai. Natalia Streltsova introduced its outreach projects.

An illness and or disability adds more complications. Lawyer Pavel Marushchak pointed out that even though there is a law that requires companies to employ persons with disabilities it is still ambiguous, and that in addition those with a criminal record are often left unrecruited. Guidance and assistance through family or a social worker would be very helpful, especially for repeat offenders.

DOCUMENTS AND LEGISLATION

When one leaves prison, the process of gathering documents is long and arduous, it falls as the responsibility for each individual to seek appropriate assistance, which is problematic as incarceration leads to the loss of certain social knowledge and communication skills. Elena Petrovskaya, coordinator of social work in the network of shelters "House of Labor NOAH", raises the question of the legal procedures. The actual housing situation is often not taken into consideration, for instance a person may have an address where he or she is registered but in fact it is not possible to live there. Furthermore if a person is not physically present at the registered address, and not available to attend the meetings with their probation officer, it adds yet another obstacle in their path of reintegration. Often men and women are released without proper paperwork. If the person, while being sentenced to imprisonment, holds a passport as a citizen of the USSR, (for instance if he or she was incarcerated in the 1990s, before Russian Federation passports came into usage) and the process to confirm one's identity is long, which in turn prolongs the process of acquiring social assistance, employment and housing. NGOs often help with restoring the paperwork.

Many of the speakers, including Lyudmila Tropina, member of the Public Chamber of the Moscow Region and Elena Antonyan, Kutafin Moscow State Law University, agreed that there is a lack of communication and cooperation between the prisons and the state bodies of social support centres between the regions of Russia, ie from the municipality where one was serving a sentence to the one where the individual will reside upon release, and the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the Penitentiary Service and the Ministry of Health and Employment of Russia. This affects housing, employment, and also applies to the medical paperwork, need to continue treatment as was noted by the lawyer Pavel Marushchak.

In her presentation, Tatiana Zrajzevskaya listed examples of fruitful cooperation in Voronez oblast between the state institution and the non-governmental initiatives as a working group. This interagency cooperation included the human rights’ ombudsman, prison officials and local entrepreneurs. In the year 2019 505 people received assistance in the form of legal aid and housing. An opportunity to work while imprisoned is a result of cooperation of the prison service and the local train factory.

Aleksey Yunoshev, representing the Office of the Commissioner for Human Rights in the Russian Federation, stated the need to create a separate service, possibly under the supervision of the Ministry of Labor and Social Development.

MEDICAL TREATMENT

Ksenia Runova, European University at Saint-Petersburg, notes that a significant length of time can pass before one can continue the medical treatment after the release. This is due to the fact that penitentiary institutions and civilian medical institutions do not have a unified database of medical documents. In other cases, some of the released persons themselves do not wish to continue their treatment, including tuberculosis, HIV, drug addiction. Currently there is no legal mechanism that oblige a former prisoner to undergo treatment upon release from a correctional institution: this poses a serious health threat for the person and the general public.

Agafonov Leonid, Human Rights Project “Woman. Jail. Society ", St. Petersburg spoke about oncology treatment in prison. Working with it as a member of a non-governmental organisation includes gaining the trust of prisoners, because any outsider is perceived as part of the system, and the clients are afraid to complain and ask for help. Help of NGOs’ to implement the legislation and fight for the release of terminally ill persons, often via the ICHR can help.

MENTAL HEALTH

Lyubov Vinogradova, Independent Psychiatric Association, pointed out that citizens with mental health challenges who are in places of detention often cannot defend their rights on their own, and sometimes may not be aware of the fact that their rights have been seriously violated. However, a law exists that enables human rights defenders and ombudsmen to visit medical institutions so as to control human rights. This helps to improve and reduce recidivism rate amongst people with mental health issues. Coercive measures of a medical nature lead to maladjustment. The reasons for this are indefinitely long terms of imprisonment, the lack of clear criteria for social danger, the unwillingness of the judicial community to take into account the results of scientific research on the duration of compulsory inpatient treatment, the unwillingness - for various reasons - of an outpatient psychiatric service, social workers and not for profit organisations to ensure the rehabilitation and resocialization of people who have discharged from psychiatric hospitals, so that they feel needed and integrated into society as a whole.

ADDICTION TREATMENT

Viktoria Osipenko, Chairperson of the Council of the Kaliningrad Regional Children and Youth Public Organization Young Leader Army, spoke about the work of accompanying young prisoners living with HIV and TB and helping them to reintegrate after their release. The challenge is that the people who use drugs often go in and out of prison, and in the context of HIV infection this frequent migration plays a big part. It was said that the correctional institutions do not rehabilitate drug users, many continue to use drugs within said institutions, some indeed begin there and become infected there. It is very important to have a mentor, to create self-help groups so a person has other activities that compete with drug use. Yulia Kuragina, Christian charitable foundation Miloserdye, shared personal experiences of looking for help to overcome drug addiction, both outside the prison system and while being incarcerated. She noted the lack of support and preventive care for prisoners suffering from addictions.

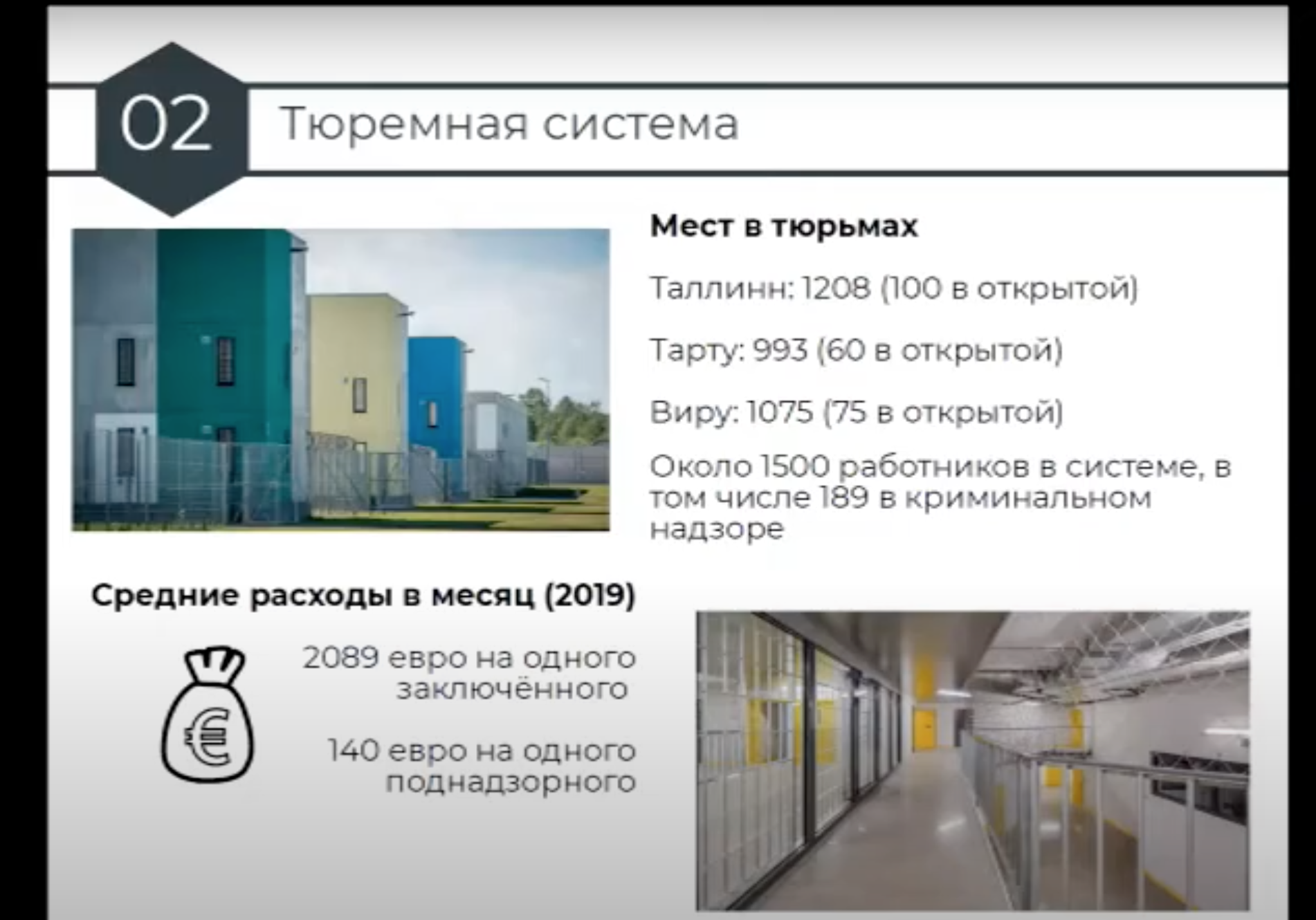

Incarceration in Estonia in numbers

Incarceration in Estonia in numbers INTERNATIONAL EXPERIENCE

Experts from all over Europe participated in the conference. Local structures of incarceration and the services for assisting rehabilitation were presented.

Solodov Stanislav, Estonia presented an EU funded project 2015-2023 which is aimed to reduce relapses by employing recently released prisoners. One participates in the program voluntarily, it provides support for integration into society with the help of a support person and provision of a place of residence. The aim of support services is to increase the participation of freed individuals in the labor market, improve their social inclusion and ability to live independently, and thus reduce relapse. The support person helps to get out without hindrance and in a safe way, provides support for integration into society. Contact between the support person and the released person is established in prison and continues on in free society. In prison, the needs of the liberated person are ascertained and prepared for release. Following a year and a half since one’s release, an action program is implemented to prevent a return to criminal activity: training in social skills and returning to the labor market. The support person cooperates with employees of regional offices, accommodation centers and the prison. The task of placement is to provide a temporary place of residence to those who have become vacant in the absence of a place of residence or its unsuitability. During the duration of the service, you can get help from a social worker, an experienced financial consultant and a psychologist, and activities to encourage participation in the work life.

José Abdon Palma Duran, University of Alicante: Spain has quite a low crime rate, however, more often than in other European countries, imprisonment is chosen as a punishment, with some of the longest terms in Europe. All prisons in Spain are public. However in Catalonia they are governed by autonomy. There are two prisons in the province of Alicante. Resocialization programs are resource-dependent. Classes are organized by the Red Cross, the Catholic Church, the Caixa Bank (social work project), the state Employment Center, the non-profit organization Project Man (helping people with substance abuse) and the Evangelical Church, which is very important for the Roma community. The Center for Social Integration in Alicante Prison is supported by the Chart Foundation, a non-profit organization, they have programs for minors, as well as programs for those who are excluded from society: these programs are run by social integration specialists, the profession is acquired by the Valle de Helda College. One of the project is designed specifically for perpetrators of gender-based or sexual violence, harassment of minors on the Internet.

Out of the 33,000 sentenced men, for 9,100 another form of correction was chosen rather than imprisonment, due to their participation in this program. The program is designed for one year, 2 hours a week, resulting in a relapse rate of only 7%. The longest term for minors is 8 years. Centers for minors in Alicante (there are two) provides 60 places. The minors are placed into small groups of 6 people. The employees of the center belong to a private foundation; there is a section of a high school inside the center. Teachers are civil servants. Thus, minors in the centers receive the same training as if they were in a regular school and receive the same qualifications as other children.

Statistics from Spain

Statistics from Spain

THE PANDEMIC

Issues such as the challenges brought about by the covid-19 were discussed, as well as methodologies how to facilitate rehabilitation process during the quarantine. The reaction of the prison officials to the global pandemic was examined. Olga Romanova Jailed Russia, listed the countries that have reduced their prison population, and temporarily released hundreds of thousands of prisoners during the pandemic, as to curtail the spread of the disease. This included Morocco, Iran, Indonesia, Afghanistan and others. She stated that no increase in the crime rates was noted with the release of the prisoners in these countries. At the same time in Russia, where no such preventive measures were taken, however, the rate of crime in the early months of 2020 increased.

The pandemic affected the work of many institutions, be it prisons or rehabilitation and support centers. Kaisa Liinanto, from Kalliola Setlementti, Helsinki, Finland, presented a rehabilitation program. There are three types of participants in the program: those who are released, under supervision or serving a sentence in prison - all have alcohol or drug addiction problems. Meetings usually take place a few times a week for several hours, they have a meal together. Participation lasts 3-6 months. The GLM (https://goodlivesmodel.com/training.shtml is used and activities include day trips, cooking together and sharing a meal, visiting libraries and museums and learning skills. During the quarantine communication took place via audio messages and audio calls. To continue the tradition of sharing meals an Easter dinner was delivered to each member of the group. Another good experience brought on by the restrictions was a more frequent communication with clients, even if relying on the means of technology. In prisons in Finland with the start of the pandemics there have been no amnesties, yet no people have been taken into custody during this time. The court hearings have been postponed until the restrictions are lifted. In prisons, since visits with relatives are prohibited due to the pandemic, video-teleconferencing meetings with families were introduced.

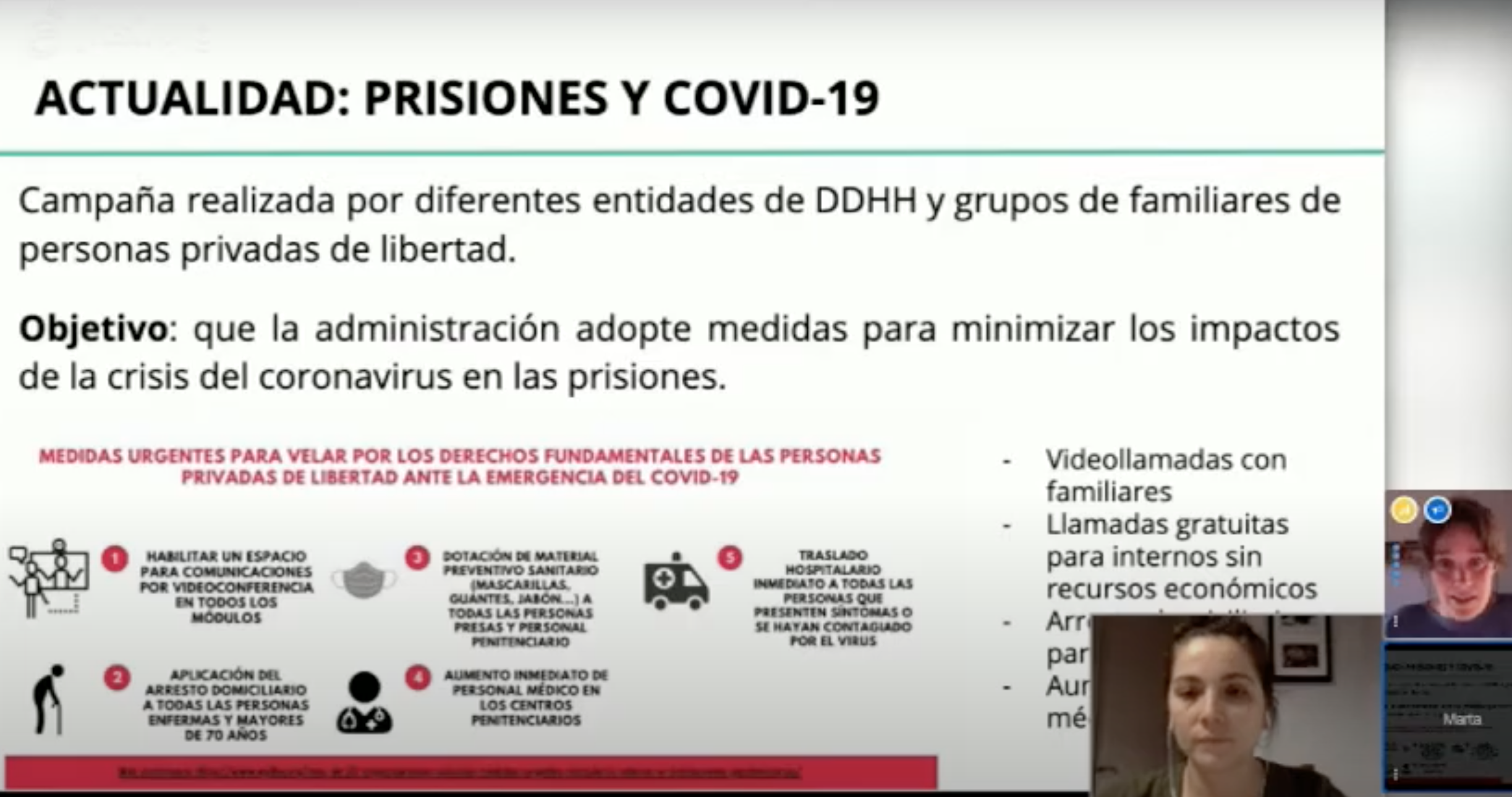

Experts from the Human Rights Center Iridia in Barcelona spoke about the measurements taken during the Covid-19 pandemic in Catalonia. Probation (in the form of community service, for example) is an option, however, more often than not a more severe punishment is chosen - a prison without any work for the benefit of society. Probation and reintegration processes are handled by external NGOs rather than the state body. During the covid, “Iridia” and the organization of prisoners' relatives were able to achieve a change in the communication that is allowed for the prisoners: now video calls are possible on demand, it is allowed to speak with relatives 1-2 times a week for 15 minutes (video, such as Skype), for low-income prisoners the calls to relatives are free of charge. Another achievement is that people in low security prisons were released to quarantine themselves at home. The main goal of the campaign is to prevent an epidemic in prison. To do this, it is necessary to disband prisons, reduce the number of prisoners in the cell, and increase the number of medical staff.

Valery Abramkin

Valery Abramkin The conference concluded with round table discussions led by Valentin Danilov, Aleksey Sokolov, Oleg Dybrovsky, and others. The need to release prisoners to reduce the spread of the covid-19 was discussed. Natalia Dzaydko, current director of the Center for Prison Reform spoke once more about Valery Abramkin’s legacy. He believed that prisons should be run locally and that a connection between people in prisons and those outside must be encouraged and facilitated.

Please see more information about Center for Prison reform here http://prison.org/

Vankila Museo

In August 2019 Arlene Tucker and Anastasia Artemeva visited the renewed Vankila Museo Prison museum in Hämeenlinna. This trip was a part of the Agents of Diversity course organised by GAP, Culture for All and Research center Cupore and focused on inclusion in an art institution.

The city of Hämeenlinna has always been known as a prison and garrison city, because these activities have been tightly connected to Häme Castle since the Middle Ages, when it was built. The Castle was used as a prison from the 1830s until 1972. In 1979, the Main Castle was opened as a museum managed by the National Museum of Finland.

Many criminals known from history have served their sentences here, such as murderer Matti Haapoja and Ostrobothnian knife-fighters Isoo-Antti and Rannanjärvi. Poet Elvi Sinervo and sleeping preacher Maria Åkerblom are among the best known female prisoners of the Castle.

In the early stages of the operation of the Prison, which was also called the Hämeenlinna penal labour prison, an example was taken from American prisons, where cells were grouped on either side of a central corridor. Previously, the prisoners had lived in shared dormitories. Today, the history and stories of prison life live on in the writings on the walls, the items, and the lived-in cells.

(https://www.kansallismuseo.fi/en/vankila/historia)

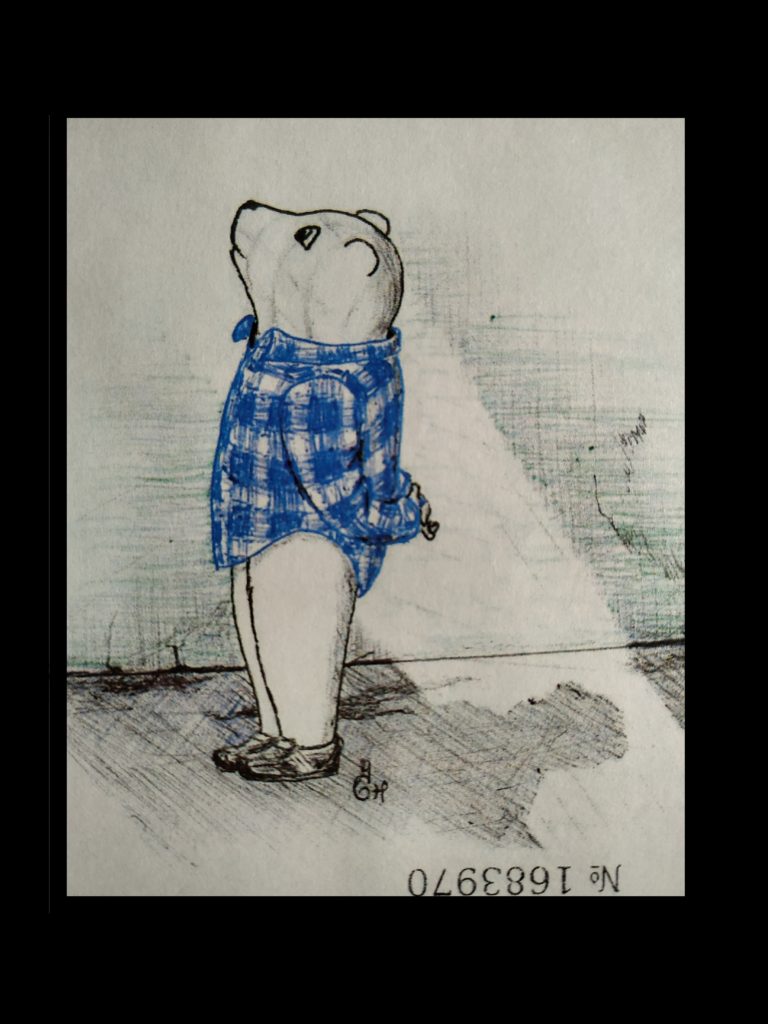

Art on the wall of a corridor where the prisoners waited to be released or tranferred to another facility.

Art on the wall of a corridor where the prisoners waited to be released or tranferred to another facility.

Some cells have been preserved in their original state of the years 1980 -1990 and still contain prisoners‘ personal belongings.

Some cells have been preserved in their original state of the years 1980 -1990 and still contain prisoners‘ personal belongings.

The guards’ room

The guards’ room Doctor’s office

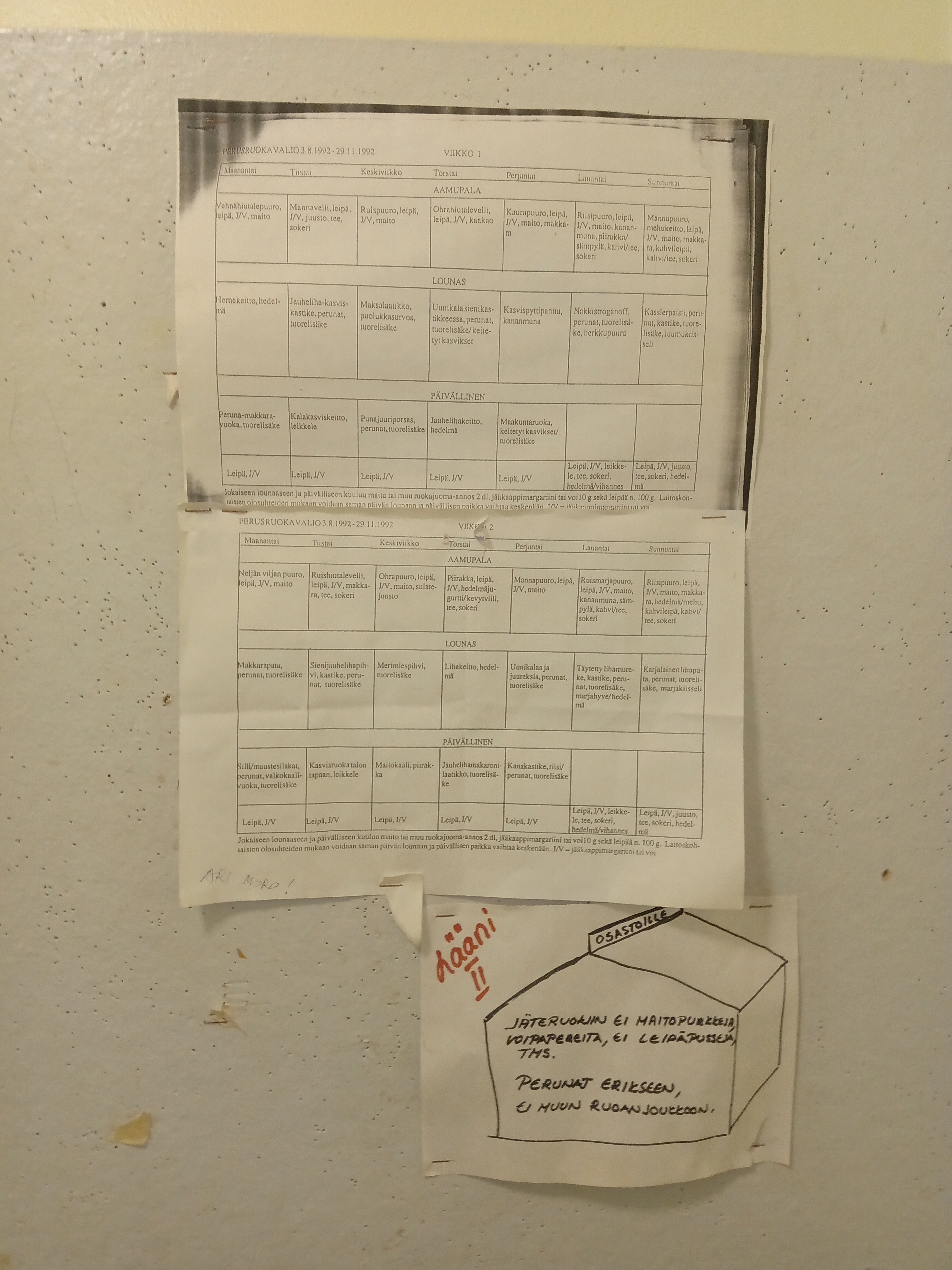

Doctor’s office Weekly schedule

Weekly schedule Items sold in the giftshop are made by inmates in prisons in Finland.

Items sold in the giftshop are made by inmates in prisons in Finland.